Does development matter?

What is development? Is it good? And where does aid fit in?

In parts of academia development is viewed as a mere construct, a discourse, a neoliberal narrative used by the West in its quest for hegemony. It’s certainly true that people in Western countries sometimes claim to be promoting development to justify actions that help no one except themselves. Neo-conservatives, for example, pretended to care about human rights to justify their invasion of Iraq. But just because words can be misused doesn’t make them meaningless. Development means something, and it matters a lot. More than almost anything on Earth.

In this article I’m going define development, explain why development is generally a good thing, and I’m going to point out one big problem with it.

Then, in following articles, coming out at the rate of one every few weeks, I’m going to look at economic development explain why it has no intrinsic benefit, but why it’s valuable nonetheless, and then I’m going to explain where aid fits into all this.

Feel free to disregard these three posts if the last thing you want to do with your summer is think about your day job. On the other hand, if you’ve ever thought about your day job and wondered why, read on…

The best explanation of development lies in a space of sorts — a gap.

This is the gap between the Sweden and the Central African Republic.

Sweden is no utopia. It suffers problems. But Swedes can expect to live on average to over 83 years of age. They can expect to receive nearly 13 years of education too. And the median Swede lives off about $57 a day. Most people in Sweden will also live safe lives free from conflict and have little reason to fear their own government.

People in the Central African Republic, on the other hand, can expect to live to just 57, go to school for 4 years and get by on $1.92 a day.1 They are living in a country that has suffered through a long and violent civil war. It’s a place where, according to Amnesty International, human rights are under constant threat.

The gap between these two countries is no construct. It represents a vast divide in the lives people get to live. The differences between Sweden and the Central African Republic also demonstrate what development entails. Development is the journey from hardship, danger and ill-health to a life that has its challenges, but which is also mostly safe and comfortable.

To be very clear, in stating that Sweden is developed — a better place to live — than the Central African Republic I am not saying the people of Sweden are in any way superior. The differences between the two countries are not a product of people’s personalities; they stem from structural features of the countries’ political economies.

When it comes to the good life, not everyone wants the exact same things and there is plenty of room to debate what matters and what matters the most, but the integral components of a good life — of development — are obvious enough when you think about what Sweden has that the Central African Republic lacks: human rights, health, and freedom from hardship. If you’re reading this, then it’s very likely you’ve had more than four years of education too. It seems fair then, to add education, and the opportunities it brings, to the list.

I’m not the first person to have wondered what development means, so it’s no surprise that the list I’ve come up with contains the three core components of the UNDP’s Human Development Index, plus human rights.2

It’s also convenient from a data perspective, because it allows me to take UNDP HDI data, combine it with survey data, and address a possible question you might have. Namely, “how do we know that what you, Terence, call development is not simply a product of your Western fixations?”

The good news is that you don’t have to ask me. People from around the world have already, in effect, answered this question when surveyed as part of the Gallup World Poll, which draws on representative samples of people in countries around the globe.

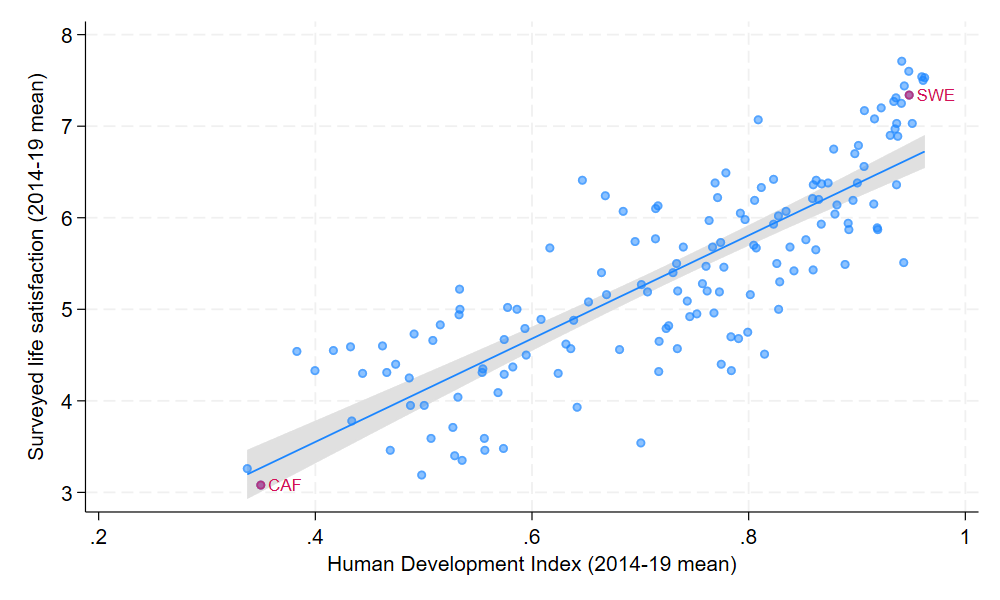

The chart below compares Human Development with the average response Gallup gets when it asks people to rate quality of their lives (which I’m going to refer to from here on as “life satisfaction”).3

Each dot is a country. Countries further to the right have higher levels of Human Development. Countries higher up the chart are home to people who, on average, say they are more satisfied with their lives. Sweden and the Central African Republic are marked on the chart in red.

The chart shows a clear positive correlation (r=0.82). There’s variation about the line of best fit, which is inevitable in social science research. It probably reflects noisy data as well as the fact that some things other than development contribute to life satisfaction. Nevertheless, countries with higher levels of human development have much higher average surveyed life satisfaction. The UN’s Human Development Index doesn’t include a measure of human rights, but when I added a standard measure into a multiple regression, both variables were clearly positively correlated with life satisfaction.4 It’s not just me projecting. People in more developed countries are happier with the lives they live. Development is, in short, real and meaningful.

Development is real and meaningful but it’s also problematic. In particularly there is the issue of environmental sustainability. I was tempted to build this into my definition of development — that is, to state that development is only genuine if it’s sustainable. But in the end I left it out so as to leave room for debate around whether development is sustainable, and whether it could ever be sustainable.

Clearly, to-date, development has not been sustainable. This is a huge problem. If the ecosystems of our planet unravel completely it will be disastrous for human wellbeing.

Perhaps, then, that’s a good reason to oppose development? After all, today’s developed countries have cooked our climate in their race to affluence.

This isn’t really an argument against development though, it’s an argument for taking sustainability into account when countries, particularly developed countries, make policy choices. The technology already exists to allow us to move away from a fossil fuel-based economy. We could do it if we tried. And, unless we do it, demanding that the world’s poor countries stay poor just to protect our environment would be impossible as well as utterly immoral. There is only one solution to the problem of sustainable development: affluent countries need learn to live sustainably and share the technologies required to do this globally.

Development is more than a mere discourse. It brings positive change to people’s lives. The challenge going forward will be creating a world where everyone benefits from development and a world where this is done sustainably.

For now though, that’s all I have to say. In the next article in this series I will discuss the most environmentally harmful, and controversial, aspect of development: economic development. Is it good? Can it be defended? Wait and see…

To read more of these posts subscribe if you haven’t already. Please also share.

Life expectancy and education data come from the UNDP’s HDI. Income/consumption data come from the World Bank via Our World in Data. Income/consumption data are in international purchasing power parity adjusted dollars and take into account the fact that the cost of living is cheaper in CAR than in Sweden. As best possible, the data also take into account consumption associated with subsistence agriculture.

There is one important difference, which is that my preferred metric of economic development is the income/consumption of the median person (or household) in a country. The HDI on the other hand uses GNI per capita. Median income does a somewhat better, albeit still imperfect, job of dealing with issues of inequality. However, GNI per capita is easier to get data on. It’s also a reasonable enough measure for the purpose of this article.

I have used 2014-19 means for both variables to smooth out the effects of any unusual years years. I’ve used 2014-19 to avoid potential data problems emerging from the Covid. The question asked was: “Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you, and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?”. This the standard Cantril Life Ladder question. Gallup asks other questions including about positive affect and about negative affect. There is a clear negative relationship between HDI and negative affect. There is a weaker, but still statistically significant, positive relationship between HDI and positive affect.

I know that correlation does not equal causation. However, it is very hard to see how reverse causality could explain the relationship shown here. The idea that people who are intrinsically more satisfied will build countries that have higher levels of development is far-fetched. It’s possible that the correlation is a product of a third variable. Something such as governance, which causes both better development outcomes and higher levels of life satisfaction, but it is very hard to see how governance, or some similar feature, could improve life satisfaction through any pathway other than by promoting development. If you want my data and Stata do files for this analysis please email me.

Amartya Sen’s ‘Development as Freedom’ has been my personal favourite definition, focused on the instrumental freedoms: political, economic, social, transparency, and security. Like you’ve noted, it does miss environmental but I think that could fit into the framing.